The Year of the Snake and Kunio Yanagida

One month has already passed in the year 2025; the Year of the Snake.

Snakes grow by repeatedly shedding its skin, and is said to symbolize rebirth. This is a good timing to shed old stereotypes and re-recognize the world, our country, and focus on your own life from a new perspective.

A few days ago, I came across a book titled “The Complete Book: The Snake in the Sky -The Life of Nikolai Nevsky-”. I thought, “Perfect for the blog in the Year of the Snake!” I picked up the book and looked at the table of contents, and saw the name “Kunio Yanagida”. As I recall, there is a memorial museum in my hometown, which is located near an elementary school. Although I had known his name since I was in elementary school, I didn’t know so much about him. Today, I met him again in the book. This must be a meaningful timing. I would like to take this opportunity to delve a bit deeper into his life.

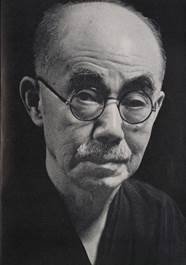

Kunio Yanagida was born on July 31, 1875 in Hyogo Prefecture, and remained many accomplishments until his death on August 8, 1962. He studied agricultural policy at the Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo), aspiring to the “study of the economy and the people”. After graduating from the university, he became a bureaucrat in agricultural administration and in 1901 became an adopted son of the Yanagida family from the Iida city in Nagano prefecture. His interest in people deepened as he came into contact with actual conditions in various parts of Japan on inspection tours and lecture tours, and he criticized conventional historiography, which focused on politics and events written in documents. He wanted to clarify the history and culture of the nameless common people, and stressed the necessity of “exploration of common people’s culture” and “study of hometowns”.

Kunio Yanagida, also known as the “Father of Japanese Folklore Studies,” investigated the stories passed down through the ages, and focused his efforts on “understanding our past”. Many of you may be familiar with his works such as “Tono Monogatari”, a collection of tales from Tono City in Iwate Prefecture, and “Kagyu Kou,” which has provided deep insights into the origins of the Japanese language and dialects in linguistics.

He continued his research in folklore studies during and after World War II, and his vast achievements, including more than 100 books, are included in “Teihon Yanagida Kunio Shu (Collection of Works by Kunio Yanagida)”.

(Photo: Kunio Yanagida)

(Reference: National Diet Library)

While I was searching about his life, the word “Esperanto” caught my attention. Esperanto is an artificial language invented and developed by Ludwico Zamenhof (1859-1917) to overcome the barrier of more than 7,000 languages in the world. In 1922, Kunio Yanagida and Inazo Nitobe had called for a resolution that Esperanto be taught in public schools around the world. After that, he interacted with Esperantist Edmond Privat, and learned Esperanto himself. He finally became a director of the Japan Esperanto Society when it was established in July 1926.

Last month, this social contribution project blog also discussed the high context of language, especially Japanese (The Feature of Japanese -High Context Culture-). One could say that taking a strong interest in a culture and pursuing it through language as a starting point is a process of getting to know themselves living in that environment. Kunio Yanagida also recognized the “Japanese language” as a “unified entity” that existed in close contact with the Japanese atmosphere. He may have tried to clarify his own roots and significance of existence by digging the Japanese language.

At the same time, learning another language is directly related to broadening one’s perspective and sense of values. Takeo Harada, the CEO of our institute said, “It is desirable to learn at least 3 languages.” Learning multiple languages also means being considerate of others. If a tourist says “Arigatou” to you in Japan, it is more gratifying than if he or she says just “Thank you”. Since Esperanto does not correspond to a specific ethnic group, country, or region, it is possible to be friendly to others without imposing one’s mother tongue on others. Therefore, Kunio Yanagida, who tried to master Esperanto for the purpose of mutual understanding among people belonging to different ethnic groups, may be said to be the ultimate pacifist in a sense.

So far, I have written about Kunio Yanagida derived from the book “The Life of Nikolai Nevsky”. I would finish this blog after introducing Nikolai Nevsky.

A Russian, Nikolai Nevsky entered the Faculty of Oriental Languages at St. Petersburg University in 1909 and became a Japanologist and Western Xia scholar. From the age of 23, he stayed in Japan for 14 years, and deeply studied the Japanese language and its culture.

(Photo: Taken in front of the garden of Nobuo Orikuchi’s house to commemorate Kunio Yanagida’s first visit to Europe. Front row, from right to left: Kunio Yanagida, Nevsky, Kyosuke Kindaichi.)

(Reference: Hatena Blog)

“While Konrad was attending the University of Tokyo at the time, Nevsky began his self-taught study of ancient Japanese culture. He first became interested in the study of the rituals of the Shinto priests. He also wanted to investigate the ways in which Shintoism was alive in the lives of the Japanese people, and he hoped to make the acquaintance of Japanese researchers in this field. He expressed this desire to the owner of an antiquarian bookstore he frequented. The human interaction between antiquarian bookstores and researchers remains a good tradition to this day. At that time, the relationship between the two must have been much closer. Conrad and Nevsky were introduced through the owner to the perfect Japanese for the purpose, Taro Nakayama. [pp.70-71]”

The above-mentioned Nikolai Konrad is known as the “Father of Japanese Studies in the Soviet Union,” a university scholar who wrote many works on Japanese literature, Japanese history, and the Japanese language, and trained many outstanding scholars and translators. It is said that there was not a single Japanologist in the USSR who did not know of him. Nevsky and Konrad became lifelong allies as young Japanese scholars during the tumultuous period before and after the Russian Revolution. From those circumstances, they met Taro Nakayama, a man who wrote multifaceted ethnohistory using many historical documents from the standpoint of popular history, and through him they were introduced to Kunio Yanagida, Nobuo Orikuchi, Kyosuke Kindaichi, Kyoko Yamanaka, Kizen Sasaki, and others. The book describes the good relationship between Kunio Yanagida and Nevsky as follows.

“Yanagida visited Nevsky at his home in Komagome Hayashi-cho on Nevsky’s fifteenth birthday in February 1916. [p.72]”

Now, I have discussed Kunio Yanagida, who deeply loved the folk history of our country, and briefly introduced Nikolai Nevsky, a Japanologist from across the sea. How different is the sight of Japan from the perspective from inside of Japan and the outside of the country? I would like to continue reading related books.

・

【References】

[Kato 11] Kato Kyuzo, “Kanbon, Ten no Hebi: Nikolai Nevsky no Syogai,” Kawade Shobo Shinsha, (2011).

※The statements in this blog are not the official views of the Institute, but rather the personal views of the author.

Chancellery Unit, Group for Project Pax Japonica, Maria Tanaka