Decipher “Knowledge Society” from Education

In the previous blog, “Who is P.F. Drucker?” I introduced the point that “knowledge” has emerged as the basis for economic and social behavior and as a central role in modern society. In addition, the position, meaning, and structure of “knowledge” have been fundamentally changed by the words of P.F. Drucker, known as the father of business administration. In this article, I will focus on educational activities as a foundation for realizing a “knowledge society”.

“Education for children” may seem a bit far to those who are actually involved in management in a company, but in Drucker’s book “The Age of Discontinuity (1969),” he discusses the importance of education for the realization of a knowledge society in “Chapter 14: Has Success Spoilt the School” and “Chapter 15: The New Learning and the New Teaching”.

The first question I would like to ask here is “what is the purpose of school?”

While it has been known that craftsmanship is a great economic asset, there is no doubt that going to school has been a kind of economic luxury. It was not until the 18th century that literacy became the foundation of civic life, as “for many years it was preachedamong the New Christians and Jews that literacy was necessary as a useful part of religious life. [P.F.Drucker69, p419]” According to Drucker, by around 1850, it was also believed that each individual needed primary education to develop the ability for self-improvement. However, only a few people needed more than a minimal education, and even fewer thought that “knowledge” was necessary for work. Drucker also points out that education was not promoted in the colonies.

At the beginning of the century, for example, there was no call for the expansion of education in the colonies. On the contrary, when the British attempted to introduce general primary education in India, the anti-colonial movement, which had already begun at that time, and which was the forerunner of the Indian National Congress, opposed it vigorously. Schools, it was thought, would be a waste of taxpayers’ money and would not benefit the country in any way[P.F.Drucker69, p419].”

Contrary to education, what the impoverished Indians needed were irrigation, roads, and tax reduction. Japanese economists also sharply criticized the illiteracy movement after 1870 as an unproductive “national prestige” scheme and a wasteful diversion of scarce economic resources.

Drucker describes Japan as follows.

“In 1967-68, Japan celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Meiji Era, and since 1867, the greatest Japanese reform of the Meiji Era, hailed by all as the greatest achievement, was the prioritization of education as the foundation of a modern, productive economy and society (p[P.F.Drucker69, p420].”

Indeed, Japanese education system may have early on provided a framework for education to train people with almost the same mindset who can find the ‘right’ answers, but it is also a sad fact that “School has become a place of general process [P.F.Drucker69, p423].”

Drucker says, “All the student can do is to show the possibilities of the future. All that the student can do in the linguistic field of school is to repeat what someone else has already done or said[P.F.Drucker69, p423].” Drucker also points out that modern society needs “people who can acquire skills on the basis of knowledge,” and that what is equally important in school education is “the training and formation of perceptual and emotional skills [P.F.Drucker69, p426].” Drucker refers to the latter by the name of Jean Piaget, a Switzerland psychologist, and says, “It is indispensable for the child to have the ability to earn a living when he comes of age and has a personality of his own[P.F.Drucker69, p426].” He also states, “The school became a place where all should learn whatever is necessary to perfect their character and acquire abilities until they reach adulthood [P.F.Drucker69, p428].”

(Picture: Jean Piaget)

(Reference: Wikipedia)

The key phrase “perfection of the child’s character” appears here. The Montessori education, a type of alternative education, has “character building” as its educational goal, which is synonymous with “perfection of the child’s character. When I tweeted about Montessori education on our official X, I received a couple of comments such as, “I know Montessori education.” “My child goes to a Montessori school.”

Montessori education was established in 1907 by Maria Montessori, the first female doctor of medicine at the University of Rome, as well as an experimental psychologist and educator. The first Montessori school in the world, “Casa de Bambini” was established in Rome in 1907. The Montessori method of education received tremendous support in the United States, and by 1913, more than 100 Montessori educational facilities had been built throughout the country. In Japan, Montessori education is mostly practiced in kindergartens and nursery schools (there are a few elementary schools), but looking around the world, it is said that more than 20,000 schools in over 140 countries are implementing Montessori education. In addition, Montessori education is practiced not only at the elementary school level, but also at the university level.

(Picture: Maria Montessori)

(Reference: Associate Montessori Internationale)

The World Happiness Ranking of Children published by the Japan Committee for UNICEF in 2021 (“Report Card 16 Worlds of Influence – Understanding What Shapes Child Well-being in Rich Countries”). In fact, more than 10% of all schools in the Netherlands, which was ranked first in the “World’s Top 10 Countries for Children’s Well-Being,” are alternative education schools, and Montessori education is the most common educational method used in those schools. Although often misunderstood, Montessori education is not only for children diagnosed with disabilities, but for all. It is also different from the so-called “early education” or “elite education” that is designed to satisfy the egos of parents who want their children to grow up to be smart. The goal of education, as mentioned above, is “character building,” or, to put it more precisely, to nurture the independence, positivity, decisiveness, concentration, compassion, and love necessary to fulfill one’s role as a person born here, by expanding and exploring one’s interests.

Drucker seemed to respect highly of Maria Montessori in his writings.

”For thousands of years people have been talking about improving teaching — to no avail. It was not until the early years of this century, however, that an educator asked, “What is the end product?” Then the answer was obvious: It is not teaching. It is, of course, learning. And then the same educator, the great Italian doctor and teacher Maria Montessori (1870-1952), began to apply systematic analysis of the work and systematic integration of the parts into a process.”

[Peter Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (1973)]

Drucker also describes the importance of the power of perception, saying, “It is primarily this power of perception, especially the power of touch and feeling, that is powerful in mental formation[P.F.Drucker69, p426].”

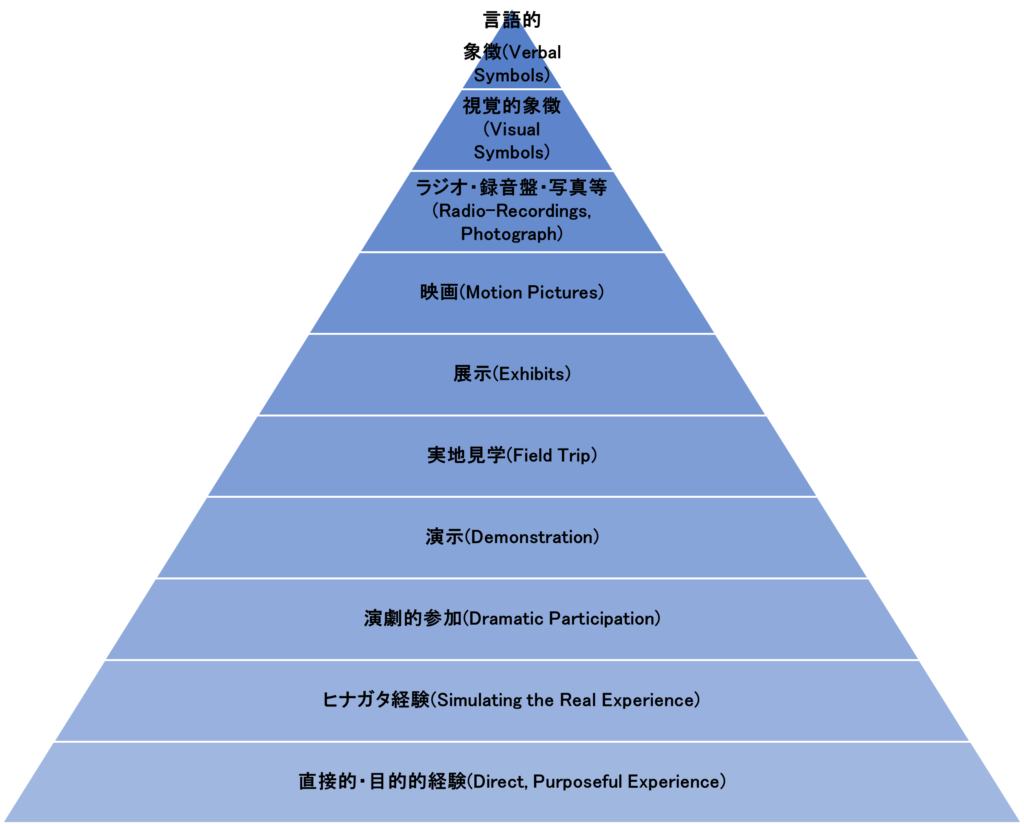

Edgar Dale (1900-1985), an American educator who developed the Cone of Experience, also known as the Learning Pyramid, also spoke of the importance of the power of perception. In “Audiovisual Methods in Learning and Instruction, Vol. 1 (1950)” written by Edgar Dale and translated by Arimitsu, a pyramid-shaped diagram appears on page 57, which is “a kind of pyramid that explains the position of each of the auditory-visual materials in the learning process and the relationship between the materials. It is “a kind of simple visual aid that explains the position of each auditory-visual material in the learning process and its relationship to each other [Edgar Dale50, p54].” From the top layer, the diagram shows “verbal symbols,” “visual symbols,” “radio/recordings/photographs,” “films,” “exhibitions,” “field trips,” “demonstrations,” “theatrical participation,” “pattern experiences,” and “direct/objective experiences,” and the lower the layer, the more direct the experience. In other words, “exhibition” is more direct than “film,” and “field trip” is more direct than “exhibition”. Let me briefly explain each layer.

(Figure: Cone of Experience)

(Reference: made by the author based on[Edgar Dale50, p57] )

“Direct/objective experience” refers to reality itself. In other words, “experiences that have an object to be seen, touched, tasted, felt, and manipulated[Edgar Dale50, p55].” The “pattern experience” is “‘the editing of reality,’ the composing of reality so that it is intelligible [Edgar Dale50, p58].” Here Dale gives the example of an airplane. For example, it’s difficult to use a real airplane to learn how to fly and understand its structure, but we can understand its basic principles by building a model airplane. This experience with models and simulators is called the “pattern experience.” Theatrical participation” is the experience of what cannot be experienced directly in the real world through dramatization (although it is obvious that there is a big difference in directness between participating in and watching). “Demonstration” can be, for example, a science experiment or a soccer coach showing by example how to pass a ball. A “field trip” could be a school excursion. In this case, the observer becomes an observer, witnessing the work and actions of the people involved. However, “if you have the opportunity to talk with a government official, the field trip enters the realm of direct experience. When observation is combined with participation, the field trip becomes even more meaningful[Edgar Dale50, p80].” Thus, it is important to understand that one level of hierarchy is not completely unrelated to the other levels of renovation. The “exhibition” is the act of looking at the items on display, while the “film” is an experience that involves contractions of time and space. “Radio, recording disc, or photograph” is interpreted as a one-dimensional material that is distinguished from other audiovisual materials and is either limited by a temporal element, as in the case of a radio, or fixed but not limited in time, as in the case of a recording disc or photograph. “Visual symbols” are charts, graphs, etc., which are abstract and not representations of reality itself. “Linguistic symbols” are words and letters. Dale says about the Cone of Experience that “we must have as many different ways of experiences as possible [Edgar Dale50, p69].”

Let me return once again to the topic of Drucker’s “Knowledge Society”.

In the past, while “work” equals “experience”, “school” and “work” were separated, and the standard was to bring what one learned in school directly into work. However, as “knowledge” came to be used on the job, the need for recurrent education emerged. Drucker said, “The more knowledge we gain, the more we become aware of what we do not know, the more we realize that there are new abilities and new knowledge to be attained, and the more we must deepen our own knowledge[P.F.Drucker69, p430]. ” Furthermore, the “expertise” needed today in the workplace is not biology or modern history itself, but its application. In Drucker’s words, “‘environmental control’ or ‘Far Eastern regional syntheses’ bring together traditional disciplines and brings knowledge that is actually useful [P.F.Drucker69, p432].” What is required of “generalists,” he explains, is the ability to take specialized knowledge and relate it to general things.

I was personally surprised that Drucker, the father of modern management, focused so much on education as an element in the “Knowledge Society”. As an adult, as a Japanese, as a manager, and as a worker… what did you think of his words and “Knowledge Society” ?

Chancellery Unit, Group for Project Pax Japonica, Maria Tanaka

※The statements in this blog are not the official views of the Institute, but rather the personal views of the author.

[References]

・[P.F.Drucker69]P.F.Drucker, Translated by Yujiro Hayashi,“The Age of Discontinuity”, Diamond, Inc., 1969.

・[Edgar Dale50, p57]Edgar Dale, translated by Arimitsu, Audiovisual Methods in Learning and Teaching (vol. 1), Seikei Times Publishing Company, 1950.