The United Nations and Dag Hammarskjold

Takeo Harada, Founder/CEO of the Institute, has selected “Michishirube (1967),” written by Dag Hammarskjold, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations, as one of the assigned books for the August summer vacation. Some of you might have read the book during this summer. In this blog, I would like to take a deeper look into his life under the theme of “Dag Hammarskjold and the United Nations.”

(Image: The book “Michishirube”)

(Reference: Misuzushobo)

Dag Hammerskjold was born on July 29, 1905 in south-central Sweden. His father, Hjalma Hammerskjold, was the Prime Minister of Sweden during World War I, a clerk of the Court of Appeal, a judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague, the Netherlands, and president of the Nobel Foundation. Eldest brother of Dag Hammerskjold was also an early member of the International Court of Justice in The Hague, and his second brother was the governor of one of Sweden’s provinces and one of the advocates of social security legislation. His youngest brother studied journalism at Columbia University and was a social correspondent for the New York Times from 1927 to 1930.

Hammerskjold himself entered Uppsala University at the age of 18, and two years later earned a bachelor’s degree in French language, literary history, and philosophy, followed by a master’s degree in philosophy in 1928, a law degree in 1930, and a doctorate in law in 1933. At the same time, he was appointed lecturer in economics at Stockholm University. He was later secretary of the National Bank, vice minister of finance, governor of the National Bank, vice minister of foreign affairs, and then, as minister without portfolio, de facto vice minister of foreign affairs, a very elite position. Although Sweden may conjure up images of a generous social security system, it was also Hammerskjold who created Sweden’s economic policies and wage stability programs.

When the first Secretary-General of the United Nations, Trygve Halvdan Lie, announced his intention to resign at the UN General Assembly on November 10, 1952, the election of his successor began.

The first three candidates were Carlos P. Romulo, a Filipino (nominated by the United States), Stanislaw Krzyzewski, a Pole (nominated by the Soviet Union), and Lester Pearson, a Canadian (nominated by Denmark), with Pearson in particular having received instructions from Great Britain and France. However, countless names of candidates subsequently surfaced, and discussions did not proceed very far, until finally Lie announced that he would consider staying on as Secretary General. For a time, it looked as if things might be back to square one. Then, French Ambassador Henri Hoppenot proposed that four names acceptable to the Americans be submitted to Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin, and if any of them were acceptable to the Soviets, that person would be named the second Secretary-General of the United Nations.

“British Ambassador Gladwyn Jebb, who was well aware of the desirable qualities of a UN Secretary-General because he had been Secretary-General of the UN Preparatory Commission, proposed, with Hopenot’s agreement, that Dag Hammerskjold be one of the four names submitted to Zorin. [B.Urquhart,S Khrushchev,et al.13]p.14”.

(The other three were Abbas Amir Entezam of Iran, Amado Nervo of Mexico, and Dirk Sticker of the Netherlands.) At this time, Jebb was already acquainted with Hammerskjold, along with Sir Stafford Cripps, the British Minister of Finance.

Regarding this, “Jebb was very impressed with Hammerskjold’s dedication to the Marshall Plan and other organizations that were just starting up in Europe. Jebb also had the opportunity to work with Hammerskjold, who at the time was the head of the Swedish delegation to the UN General Assembly. Although not widely known as an international figure at the time, Hammerskjold had an outstanding reputation among those with whom he worked. [B.Urquhart,S Khrushchev,et al.13]p.14.”

Thus, on March 31 of the same year, after much informal discussion and deliberation, Jebb informed the Security Council that the permanent members had reached an agreement to recommend Hammerskjold, and on April 30, 1953, Hammerskjold officially became the second Secretary General of the UN.

(Image: Dag Hammerskjold)

(Reference: The Nishinippon Shimbun Co., Ltd.)

Let’s look into Hammerskjold’s personality.

In a speech, one year before he became a member of the Swedish Academy, he said this from a passage in Brown: “All men are microcosms.

He quoted the words, “Since every man is a microcosm, creating the whole world around him, there can be no such thing as a lone man,” and then asked, “Can we escape this conclusion? [R. Mirror62] p. 23.”

Hammerskjold sometimes spoke with a mysticism that is common to all religions, and in the meditation room of the United Nations he said like this.

“In the meditation room of the United Nations, he said, “When we are in deep contemplation, when we come to the source of our desire, we are alone, we feel heaven and earth, and we hear the voice of our inner heart. [R. Mirror 62] p. 23.

The book follows,

“From this mysticism arises the view that Hammerskjold was a dreamy idealist, a kind of superworldly nationalist. But those who worked with him considered him more of a dream-breaker and a realist. -Hammerskjold was what one might call a pragmatic idealist, with a keen sense of feasible and timely solutions. He looked at a situation with intellectual candor, sifted through the correlations between the essentials and the variables, and then, in the spirit of the Charter, devised feasible solutions and interim measures. [R. Mirror62] p. 23,24.”

Hammerskjold’s attitude toward the position of Secretary-General of the United Nations, a position he held for seven years, is expressed in his own words in a book titled “The Secret of Successful Mountain Climbing:” (He was a great mountaineer, president of the Swedish Alpine Club and vice president of the Swedish Tourist Federation.)

“Never move without knowing where to put your foot next. Never move without knowing where to put your next step, and never move without feeling secure enough to take that step completely. Those who are truly determined to reach the summit will not take a gamble of hastily jumping on an uncertain foothold or an unreliable clue. If they know exactly what the end goal is, they will focus their efforts on the problem at hand. Because if this is not resolved, all talk of the summit will be a vain nonsense. [R. Mirror 62] p. 24,25.”

His words paint a picture of a very wise and intelligent man.

“The United Nations” may sound like a bunch of nations, and even more, like egos of nations clashing with each other, and nothing progressing, but Hammerskjold’s thought has no such thing. The fact that Hammerskjold was a supranational entity, pursuing his activities with an independent will, comes into view.

Let me close by introducing a passage from the book, “Michishirube(1967).”

“No authority other than the United Nations, no government other than that of the United Nations, can be expected to be able to act as an instrument of peace.

We seek no direction from any authority or any government other than the United Nations [D. Hammarskjold67], p. 8.”

This sentence seems to indicate that Hammerskjold himself interpreted the UN as a holy thing that transcended even the state.

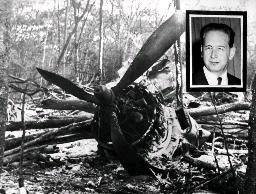

With the above background, Dag Hammerskjold was killed in a plane crash bound for the Congo in 1961 while fulfilling his duties as Secretary General of the United Nations.

(Photo: UN Secretary General Hammerskjold died in a plane crash in September 1961.)

(Reference: The Nishinippon Shimbun Co., Ltd.)

He had mediated during the Congo uprising, but was cornered between the major powers and finally headed there when he had no choice but to get on board himself, and the plane crashed. Would you consider this just an accident? I hope that further investigation will reveal the cause. (If you would like to learn more about the Belgian Congo, the worst colony in African history, please consider purchasing the Institute’s Monthly Report (September 2019), URL: https://haradatakeo.com/ec/products/1210)

We hope that this blog has provided you with the essence of Dag Hammarskjold, and I hope you understand that his kind of thinking underlies our Institute’s efforts to engage with the United Nations.

Chancellery Unit, Group for Project Pax Japonica, Maria Tanaka

※The statements in this blog are not the official views of the Institute, but rather the personal views of the author.

[References]

・[B.Urquhart, S Khrushchev,et al.13]“The Adventure of Peace : Dag Hammarskjöld and the Future of the United Nations”, Palgrave Macmillan,2013.

・[D. Hammarskjold67]Dag Hammarskjold,translated by Nobunari Ukai,“Michishirube”,Misuzu-shobo,1967.

・[R. Mirror62]Richard・I.・Mirror,translated by Yuzou Hatano,“Sekai Heiwa eno Ishi: Hammarskjold Souchou no Shougai(The Will for the World Peace: The Life of President Hammerskjold)”,Nihon gaisei gakkai,1962.